Orthodox Christianity in Southern Italy

St. Gregory of Cassano

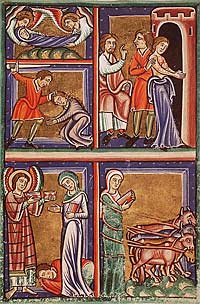

Scenes from life of saint Agatha of Palermo1. Introduction

“ The history and the spirituality of the Italo-Greek monks in Byzantine Southern Italy and Sicily is the account of a people faithful to their Orthodox Faith and their Byzantine culture in circumstances that were at times difficult and in territories that were at the extremes of the empire centered in Constantinople.These people found in Calabria, Puglia and Sicily were the proud heralds of a way of life that stretched across the vast expanse of the Byzantine Empire from Asia Minor to Southern Italy.”[2] These lands of Southern Italy and Sicily, once called “Magna Graecia,” were for centuries a hearth of Orthodox culture, strongly dominated by Orthodox monasticism. Prior to and even for a short time after the Schism of the Latin Church (a.d. 1054), Southern Italy was a land of Orthodox saints. The entire Church tradition of the Orthodox East was strongly championed in this region.

The span of about seven centuries within which Byzantine civilization and monasticism flourished in Southern Italy can be divided into three historical periods: the Byzantine period, the Saracen (Arab) domination, and the Norman conquest.

2. The Byzantines in Italy

The Roman Empire was divided into western and eastern portions during the reign of the pagan emperor Diocletian (284–305). By 325 St. Constantine, the first Christian emperor, had defeated his pagan opponents and unified the empire. For strategic reasons he moved his capital from Rome to the ancient city of Byzantium in 330, renaming it Constantinople and designating it as the “New Rome.” The empire was split again into eastern and western halves by Constantine's sons. It was reunified under Emperor Theodosius I in 394, but after his death it was again split, this time permanently.The Roman military power in the West began to decline soon thereafter, and Italy was subjected to attacks and subjugation by numerous enemies.

Toward the beginning of the fifth century, the Visigoths invaded the Italian peninsula and conquered much of the western portion of the Roman Empire, sacking Rome in 410. The city was sacked again in 455, this time by the Vandals. In 479 the Ostrogoths crossed the Alps and by 493 conquered all of Italy except Sardinia.

Beginning in 535 the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I began the GothicWars to win back Italy for the Roman Empire. After an exhausting series of campaigns which severely drained the empire and devastated much of Italy, Justinian brought Italy and Sicily under Byzantine rule in 552. This was a short-lived victory, however. In 568, three years after Justinian's death, Northern Italy fell to the invading Lombards, who slowly advanced south.

Nevertheless, the area of Southern Italy, consisting of Sicily, Calabria, and Puglia, remained under control of the Byzantine Empire. Civil and military authority was placed in the hands of the Exarchate of Ravenna in 584, where it remained until the Lombard conquest of Ravenna in 751. Although this region was often ravaged by war, a strong Byzantine cultural and monastic presence formed there and persisted until the eleventh century.

Ecclesiastically, these Italian territories were at first under the jurisdiction of the Roman patriarchate. Prior to the development of Greek monasticism in Southern Italy, which began to spread in the seventh century, there were already numerous monasteries throughout the area. During his papacy, St. Gregory the Dialogist (590–604) strongly favored the Latin element in the Church; yet there were known to be Greek monastics, including one bishop, in Sicily. In the writings of St.Gregory, mention is made of twenty-two monasteries in Sicily and four in Calabria. But within decades after St. Gregory's repose, the culture and monastic life, first of Sicily and then of the rest of Southern Italy, came more and more under the influence of Byzantium. Among the factors that contributed to this increase of Greek influence were the Persian invasion of the Near East between 611 and 618, which brought Syria, Palestine, and Egypt under Persian control, and the subsequent Saracen conquest of the same area, beginning in about 633. The Persians favored the monophysite heretics living in these areas and began to persecute the Greek-speaking people who were loyal to Constantinople and supported the Orthodox teachings of the Fourth Ecumenical Council (Chalcedon, 451). Although the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius drove back the Persians by 629, he himself tried to impose yet another heresy, monothelitism, upon the empire, causing further agitation and strife. The Saracen conquerors of the Levant likewise favored the monophysite heretics over the Chalcedonians. The unrest caused by this situation in turn brought about the flight of Greek-speaking Christians, especially those of the educated and ruling classes, from the Near East to North Africa, Asia Minor and Italy. The emigrants who fled to Italy augmented the Greek-speaking populations that had already been present in Southern Italy and in Rome for several centuries. Due to the social standing of these new arrivals and their easy assimilation into the already-presentGreek culture in parts of Italy (especially Sicily), the societal balance of these localities quickly tilted away from Latin and towards Byzantine culture.

In Rome too, at the beginning of the seventh century, a large and significant community of “Greeks” (those fleeing from different parts of the Eastern Roman Empire), immigrating from several areas of the Mediterranean, began to form. These immigrants built numerous churches and basilicas. This was similar to what was occurring in Ravenna and elsewhere during the Byzantine Exarchate. At the Roman Synod of 649, convoked against monothelitism by St. Martin, pope of Rome, Eastern monks played an important role in the proceedings. Furthermore, during this historical period the Church of Rome began to elect Greek popes. Between 642 and 772, almost uninterruptedly, thirteen of the Roman popes were of Eastern origin, and many had lived in Sicily before moving to Rome.

During this period there took place the Byzantinization of Sicilian culture and of the administrative and economic framework of Southern Italy, as well as of the liturgy.

3. The Iconoclast Period

During the eighth century two events occurred which greatly affected the life and development of the Italo-Greek Church in Southern Italy and Sicily: the iconoclast controversy and the shift of the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Southern Italy and Sicily from Rome to Constantinople.In about the year 730 the Byzantine Emperor Leo III (the Isaurian) issued an edict forbidding the veneration of icons throughout the empire. A fierce persecution of iconophiles ensued, especially of the monastics, the primary defenders of the veneration of icons, whose monasteries were destroyed and who were banished, tortured, and put to death. The Roman popes, however, remained adamant in their opposition to iconoclasm. Popes Gregory II (715–731) and Gregory III (731–741) refused to accept Leo's edict, and at a local synod in 731 excommunicated the iconoclasts. Leo responded by severely taxing papal property holdings in Sicily and Calabria, eventually seizing them.

Finally, between the years 732 and 757, the emperor attached the hellenized territories of Sicily and Southern Italy to the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. Besides the iconoclast controversy, another compelling reason for this move was the alliance of the Roman popes with the Frankish kings, beginning in 754, in order to forestall attacks by the Lombards. From this time on, until the late eleventh century, Sicily and Calabria were entirely Byzantine, both ecclesiastically and culturally. The Italo-Greek bishops no longer participated in synods of Rome, but became quite active in synods in the East, particularly at the Seventh Ecumenical Council (of Nicea) in 787, which condemned the iconoclastic heresy. It was after this council that Bishop Gregory of Syracuse was sent back to Southern Italy to reintroduce the veneration of icons.

4. Saracen Domination

Beginning in about 637 with the fall of Jerusalem, Saracen invaders spread inexorably throughout the Middle East, the Mediterranian, North Africa, and eastward to Central Asia. While many Greek-speaking refugees came to Sicily and Southern Italy during the seventh century, these areas were also subject to continual raids and occupations by Saracens from 652 until the Norman conquest of Sicily in the late eleventh century. Beginning in 827, Muslims from Spain and Morocco began the conquest of Sicily, which took almost 140 years, due to the strenuous resistance of the local Italo-Greeks. At the same time there were also especially severe Saracen invasions of Calabria, Puglia, and Campania in 839–840, after which the Saracens occupied much of these provinces. However, in 875 the Byzantines began the reconquest of Southern Italy, which was finally accomplished ten years later. There followed the complete political and ecclesiastical reorganization of the territory.From this time on the Saracens no longer occupied Southern Italy, but periodically engaged in numerous destructive raids, resulting in the slaughter of many Christian inhabitants or their capture and sale into slavery in North Africa.

In Sicily, while Christianity did survive under the Saracens, and some churches continued to function within the limits of Islamic law, there was still a systematic campaign of humiliation and proselytism which, along with the instability caused by local wars and famines, led to a certain amount of Islamization. As the Saracens moved eastward in their conquest of the island, Orthodox Italo-Greek inhabitants, among them many monastic saints, moved as well, eventually settling in Calabria or further north, especially in the Mercurion and Latinianon (northern Calabria), while still others migrated to Greece or even further east. Saints from this period who moved to Calabria include St. Elias the Younger (†903), St. Elias the Speleot († ca. 960), St. Leo-Luke of Corleone († 10th c.), and the monastic family of Sts. Christopher, Kale, Sava and Macarius († 10th c.). Those who moved further north include St. Fantinus the Younger († ca. 1000), St. Nilus the Younger of Rossano (†1004), and St. Bartholomew the Younger († ca. 1054). Finally, those who moved further east — toGreece, Constantinople, Sinai, Mount Athos and other eastern Mediterranian areas — include St.Methodius, Patriarch of Contantinople (†847), St. Joseph the Hymnographer (†886), St. Athanasius of Methone († ca. 880), and St. Symeon of Syracuse (†1035).

5. Monastic Life in Southern Italy

As a result of the Saracen invasions there is little information preserved about the monastic life of the Italo-Greeks before the ninth century. But, beginning with the ninth century, the written Lives of the Calabrian and Sicilian saints provide many details about the monasticism of Southern Italy.The available records of Sicilian and Calabrian monasticism point to the presence of both eremitic life and various forms of coenobitic life, depending on the time period. The coenobitic way of life that existed during the seventh century gave way to a more eremitic form largely due to the iconoclast controversy, which had a negative effect on Italy as well as on Byzantium. Since monastics felt the full force of the persecutions, it became difficult for them to form larger communities, and thus they lived either alone or in small groups. Another factor that contributed to this movement was the series of Muslim raids on Sicily. Both of these circumstances naturally favored the development of the eremitic life among these monastics. Typically they spent their time in prayer, ascesis, spiritual reading, and silent work. They had little contact with the outside world and often moved from place to place because of their love of silence, their desire to escape fame, and the need to escape the Saracens.Occasionally, as in the case of St. Elias the Speleot, these small groups would eventually form coenobitic communities. An area particularly rich in monastic dwellings was that of theMercurion and Latinianon. The natural surroundings — forests, mountains, ravines, caves and grottos — provided an ideal environment for hermits and small monastic communities. These settlements were interconnected and even formed a kind of monastic federation, with St. Sava, and later his brother Macarius, originally of Sicily († 10th c.), as their common elder. Among the other monks who dwelt in this area at one time or another were St. Fantinus, St. Nilus the Younger of Rossano (†1004), and St. Nicodemus of Kellarana († ca. 1020). It is interesting to note that the above-mentioned monastic federation existed at about the same time as similar federations onMount Athos, atMountOlympus in Bithynia, and in Klarjeti and the Davit-Gareji wilderness in Georgia, a fact which demonstrates how akin the monasticism of Southern Italy was to that of the rest of Byzantium and the East.

The monasteries seldom consisted of stone buildings. More frequently they were located on a simple country lot surrounded by a palisade, within which (depending on the lay of the land) were scattered huts, small cells, and caves, which served as shelters and places of worship. They were simple and primitive, and often abandoned when the inhabitants either sought greater solitude or fled from the Saracens. The custom these monks had of moving from place to place is reminiscent of the way of life practiced among the Egyptian Desert Fathers and the Celts of Ireland and Scotland.

At times some of the monks living together in the same community dwelt in solitude, while others lived in small groups of two or three, alternating periods of solitude with periods of communal life (liturgical prayer, meals, and spiritual instruction) under the spiritual guidance of the monastery's elder. Others lived in succession within the different forms of monastic life, moving from coenobitism to eremitc life and back. Such were St. Elias the Younger, St. Vitalius of Castronovo, and St. Nilus the Younger. There were generally no fixed rules governing the details of daily life. The community was centered around their elder, who often lived apart.

While during the ninth century the level of education among the monastics was not high, this gradually changed in the tenth century. Monks then began to study and copy various manuscripts, among which were liturgical and scriptural texts, Greek patristic works (such as those of St. John Chrysostom, St. Basil the Great, and St. Theodore the Studite), and the Lives of various saints of the East. Few of their written commentaries were local in origin; most were the works of the Holy Fathers.

However, by the end of the tenth century an abundance of hagiographical material, as well as hymnography, began to appear.

The Italo-Greek monastics played an important part in both the civil and ecclesiastical life of that era. They had a great rapport with the local people, who would come to them for prayers, blessings, counsel, and other kinds of help. This in turn gave them great freedom in dealing with both civil and Church authorities, who as a result interfered little with the life of the monasteries. Rather, bishops and civil leaders often came to the monastics for spiritual guidance.

The monks also excercised a prophetic role in dealing with secular authorities, admonishing them for wrongs committed and defending those wrongfully accused or excessively punished by them.

Finally, the coenobitic monks greatly affected their immediate environment by their assistance in the formation of rural settlements and communities. This occurred when monastic communites began to clear the land around their monasteries to make it arable. By cultivating the land they not only provided their own sustenance but attracted the local peasants, who helped them in their work and eventually settled nearby. The land became more productive and drew other local people, and so previously uninhabited areas became settled. A movement of this type was repeated in Northern Russia from the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries.

5. The Norman Conquest and the Decline of Byzantine Influence

By the middle of the eleventh century the tension between the Churches of Constantinople and Rome, which had begun centuries earlier, had greatly increased. Among the causes for this were exaggerated claims of universal papal authority over the rest of the Churches, the insertion of the “filioque” clause into the Nicene Creed, novelties in some of Rome's liturgical practices, and disputes over local jurisdiction in the Balkans and Southern Italy. This culminated in the Schism of 1054 and the mutual excommunications of the Byzantine and Roman Churches.At the same time, the Normans began a series of attacks, winning their first battles against the Byzantines in 1041. At first Pope Leo IX opposed the Normans, and was even willing to ally himself with the Byzantine emperor Constantine IX Monomachus against them. However, due to the above-mentioned theological dispute, the papal legates, sent to Constantinople to negotiate this, instead entered into polemical arguments with the patriarch, and ended by excommunicating him, thus precluding an alliance. By 1071 the Normans took all of Southern Italy, and by 1091 they completed their conquest of Sicily from the Saracens.

In 1059 the next pope, Nicholas II, desiring to increase papal power and reestablish authority over Southern Italy, met with the Norman leader Robert Guiscard and recognized him as the “Duke of Puglia and Calabria and future Duke of Sicily” in exchange for Robert's oath of loyalty to the pope. Robert swore to place all the churches in his state under papal jurisdiction, and thus the survival of these churches came to depend on their recognition of Rome's jurisdiction. Robert considered Constantinople his enemy, and so to assure loyalty to himself in Southern Italy he gradually replaced the Italo-Greek bishops with Latin ones or found Greek bishops who would be loyal to Rome. In Sicily, still occupied by the Saracens, the minority Orthodox Christians at first thought of the Normans as their liberators, and in fact helped them to take the island from the Muslims, a process that took about thirty years. The Latinization of Southern Italy and Sicily was a slow process. In Calabria the Normans replaced Greek bishops when they could, and when this was not possible due to local opposition, they exacted only loyalty to Rome. Although some dioceses remained Greek until much later (Gallipoli in Puglia remained so until 1513), the majority were Latinized far earlier. Opposition to Latin domination continued for quite some time among the clergy, who in general identified themselves as Byzantines. Many monastics remained Orthodox until the twelfth century. In Sicily, due to the ecclesiastical disarray caused by long years of Saracen control, the Norman count Roger I (1071–1101) set about the reorganization of the Church, appointing numerous Latin bishops.

At the beginning of the Norman takeover of Southern Italy, many small monasteries, especially in the northernmost areas, were devastated. Robert began to encourage Benedictine monasticism throughout the territory so as to offset the influence of Italo-Greek monasticism, giving some of the Greek monasteries to the Benedictines as dependencies. The situation was different in Sicily, where the Normans endowed Italo-Greek monasteries in an effort to win the loyalty of the population. In addition, Roger I and his son King Roger II came to admire the Byzantine civilization and culture, and many Italo-Greeks served in the Norman government.

As Roger I consolidated his power in Sicily, his policy became one of appointing Latins to high ecclesiastical office, while allowing the Italo-Greeks to hold onto their monasteries and churches, even founding new ones himself, such as the monasteries of St. Michael of Troina and St. Elias of Ebulo. His son continued this policy for much of his reign, founding fifty-three Italo-Greek monasteries by 1134.

During the Norman rule, which now offered external economic and political stability, Italo-Greek monasticism gradually changed to emphasize coenobitism, with large endowed monasteries governed by set monastic rules, such as those of St. Sabbas and St. Theodore the Studite. Eremitic life still existed, but was now more of an exception. Monasteries became much larger, with many churches, buildings, libraries and scriptoria. In addition to spiritual literature, secular literature and the classics were studied. The previous informal federations of monasteries were replaced by a more rigid and institutional framework. Reasons for this change include the strong Latin influence on the Italo-Greek monasteries, the decline of the standard of monastic life in these monasteries during the eleventh century, and the desire of the Normans to replace the spiritual bond that had joined the Italo-Greek monasteries to Constantinople with a more juridical bond under their own authority — and gradually under the authority of the Latin popes. In addition, the Normans were also attempting to fit Italo-Greek monasticism into their concept of feudal society. On the other hand, there was already a movement from within these monasteries to institute the earlier reforms of St. Theodore the Studite, which emphasized coenobitism and defense of the Faith. All of these elements worked together in varying degrees to bring about a revival of the quality of monastic life, which had suffered desolation in Sicily from the Saracens and in Southern Italy from the initial Norman invasion.

This revival was, however, short-lived. By the twelfth century the Greek-speaking population of Sicily and Southern Italy had been effectively cut off from the spirituality and culture of the Byzantine East. The Latin population and culture around them grew and gradually absorbed them, causing decadence among them and their monasteries. In Sicily, nowthat the Saracen threat had decreased Roger II no longer needed the support of the Italo-Greeks and began to give greater support to the Latins. At last, as Latinization increased, during the fouteenth century the Italo-Greeks either emigrated to the East or lost their identity, and the great flowering of Orthodox monasticism in Magna Graecia came to an end.

Nonetheless, today, with the monolithic character of Roman Catholicism beginning to wane in Southern Italy and Sicily, the great heritage of the region's Orthodox saints remains firm. With the new immigration to these lands of Orthodox people from Eastern Europe and the conversion of local Italians to the Orthodox Faith, the Orthodox Church and its monasticism are beginning to reemerge. In recent decades it has become possible once again to offer an Orthodox witness in the land of Southern Italy. Through the prayers of the Orthodox saints of Italy, may it be so! Sources:

Fr. David Paul Hester. Monasticism and Spirituality of the Italo-Greeks. Thessalonica: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies, 1991. Hieromonk Alessio. I Santi Italo-Greci Dell ‘Italia Meridionale; Epopea Spirituale Dell ‘Oriente Cristiano (The Italo-Greco Saints of Southern Italy: The Spiritual Epic of Eastern Christianity). Calabria, Patti [Messina]: Nicola, 2004. Iconographic sketches throughout this Calendar are by Luigi Merulla, from Hieromonk Alessio's book.

Thanks to Fr. David Hester, Deacon Joshua and Diaconissa Lucia Resnick, and Giovanni Tallino for their assistance.

For further information on the Saint Herman Calendar contact St. Herman Press:

St. Herman Press, P.O. Box 70, Platina, CA 96076