Monastery of Hosios Lukas

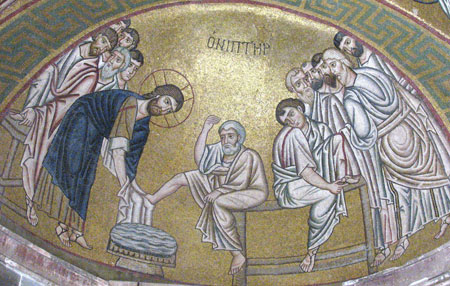

Christ washing the feet of the Apostles

The Monastery of Hosios Loukas, one of the finest, 11th century Byzantine monuments in Greece, is set on a picturesque slope on the western foothills of Mount Helikon, near the ancient town of Steiri.

The monastery’s two large churches (the Church of Panagia and the Katholikon), its Crypt, belfry, monk’s cells and other buildings, all devoted to the local, miracle-making Hosios, have a unique standing as they are considered paragons among all 11th century monuments in Greece.

Our main source of information on the monastery and Hosios Loukas himself is his Life (Vios), compiled by an anonymous disciple in 962 AD, a few years after the Hosios’ death in 953 AD.

The ascetic Hosios owed his close relationship with the generals in charge of the Helladic Thema, based in the then thriving town of Thebes, on his divine charismas. The generals Pothos, son of Leo Argyros, and Krinitis Arotras, both honoured the Hosios. Krinitis, in fact, began building, at his own expense, a church devoted to St. Barbara during Hosios Loukas’ lifetime.

Two years after his death, his disciples and fellow ascetics completed and adorned the Church of St. Barbara, turned the cell in which the Hosios was buried into a cross-shaped oratory and built new cells and visitor dorms. A new monastic community was thus established by 955 AD. According to E. Stikas, the Church of St. Barbara is in fact the Church of Panagia and the oratory is the present-day Crypt.

The erection of the Katholikon, which is chronologically set in the first decades of the 11th century, has been attributed by tradition, to three Byzantine Emperors: Romanos II (959-963 AD), Basil Bulgaroktonos (976-1028 AD) and Constantine IX Monomachos (1042-1055 AD).

In 941, Hosios Loukas foretold that “a Romanos will take over Crete”, referring to the island’s occupation by the Saracens. When asked if he meant the current Emperor, Romanos I, he answered: “not him, but another.” The erection of the Katholikon is therefore connected to this prophecy, for it would be only natural for the Byzantine Emperor Romanos II to want to build a majestic church out of gratitude to Hosios Loukas for the liberation of Crete (961 AD), which he foretold. Romanos I, however, died in 963 AD, only two years after the restitution of Crete. This two-year time-frame is not considered to have been adequate for the realization of such a majestic project.

There is no concrete evidence to support that the erection of the Katholikon took place during the reign of Basil Bulgaroktonos, as this most important event is not mentioned in the detailed, written descriptions of the Emperor’s triumphant march from Achris to Athens (1018-1019 AD).

In contrast, the possibility of Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos having contributed to the erection of the Katholikon has been widely supported because: a) there was a great flourishing in the arts and literature during his reign and huge amounts of money were spent on the establishment of majestic churches and public welfare institutions, and b) according to a particularly important piece of information recorded by the explorer Cyriacus of Ancona (1391-1455 AD), the Katholikon was erected during the reign of Constantine Monomachos (1042-1055). Cyriacus visited the Monastery during his tour of Greece (late 1435-March 1436 AD) and recorded his passing on an inscription within the church where he mentions that it was built by Constantine IX Monomachos and that he had read this in an old book he found at the Monastery. The theory which connects the erection of the majestic church to the aristocracy of the then prosperous town of Thebes is refuted by the size of the building, its type and the value of the materials used to construct it, which are all indicative of rich, imperial treasuries and of artists used to decorating imperial buildings. The title Vassilomonastiro (king’s monastery) reflects the monument’s richness and perfection as observed by later generations.

At this point, it is worth recording the historian Const. Paparrigopoulos, who supports that the erection of majestic churches during this era was a form of religious counterattack after the period of iconoclastic controversy and addressed the imperative need for national unity after continuous, barbaric invasions. Moreover, the late Pr. Aggelos Prokopiou suggests that the Monastery of Hosios Loukas was formed as a centre for the renaissance of Orthodoxy, a glorious monument for the victory in Crete but also as a shinning beacon for the hellenization of heathen peoples who had settled in Greece.

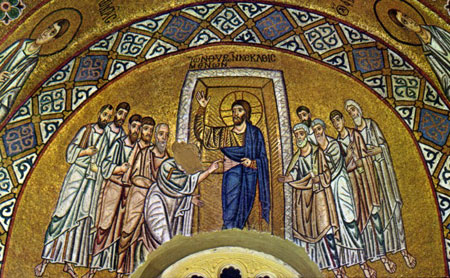

Photographs of mosaics